Turning The Norm Upside Down

What’s in a sari pallu thrown back over your shoulder or the customary pallu (drape) falling in front? Everything in Kailas’s case.

Kailas was a member of the karobari samiti (member of the executive committee) of Ujaas. She embarked on her journey of empowerment as a member of a self-help group initiated by Aatapi in her village. “A monthly saving of 50 rupees transformed my life.”

“I have grown from a diffident woman who could not say ‘shoo to a fly’, or signed the minutes of a meeting without reading them in the initial years, to a woman who can now stand up for what is right – be it my family, community or any sarkari adhikari.”

Kailas like most women from rural Gujarat wore her pallu seedha, falling in front, the Gujarati style drape. “Deep in my heart, I always nursed a wish to wear my sari with the pallu thrown back over the shoulder, like many of the women from the cities. But I never had the courage.”

“Or so I thought…A soiled sari won’t taint my character, but if I drape my sari pallu the reverse way around, front to back, I will be labelled a woman of loose character. Perhaps be thrown out of the house by my mother-in-law or husband.”

“A training programme changed my thinking… On the last day of the training programme I draped my sari pallu undha, (the reverse way) flowing back across my left shoulder, transgressing from the norm. “I think I looked very smart. I wore my sari in the dakshini (western) style through the day. And, I decided to wear it home!” She laughed still surprised by her bold act.

“My daughter loved it, but was nervous about what her father would say.

“Now that I have finally done it, I will wait to see hm explode, I told her.

“When my husband came home, his eyes popped out of his head. First the pink sari, our Ujaas uniform, which marked the beginning of my rebellion, and then this audacity, the undhi sari!”

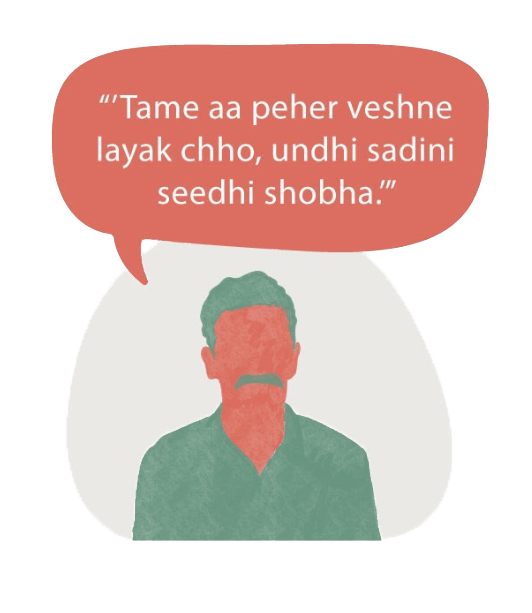

“’Tame aa peher veshne layak chho, undhi sadini seedhi shobha.’” he whispered, the pride in his voice apparent. Loosely translated he complimented me. You have earned the dignity to wear your sari in this liberated style by your deeds.”

Kailas’s simple break from tradition was an act of crossing the lakshman rekha– the social ‘line of control’ for women. It signified going up the social ladder, moving away from the fetters and limitations of wherever one came from, with its sense of limited identity and origins.

Through this simple yet courageous act Kailas had asserted and acknowledged her citizenship as an equal among equals.

As activist poetess Sabika Naqvi wrote in her poem Meri sari ‘You thought my saree is a mark sheet of how cultured I am. No. It is that nine-yard cloth in which I have wrapped my identity and existence.’ Kailas no longer works with Aatapi, she is now employed by an international NGO and earns a very respectful salary. Aatapi is very happy to have been the catalyst in her growth story.